Archive Highlights

From the Archive: Death and the springtime garden

In January 1868, a child at Cotesbach looks forward to the plants and flowers that the changing seasons will bring and imagines a conversation between gardeners. Idyllic – except that the scene is an allegory and one whose significance was so soon to overshadow the family.

The text of document .2165.1 looks like a carefully executed child’s handwriting exercise but its theme, with uprooted plants and cut flowers, is untimely death. This, of course, was a fact of life in mid-nineteenth century families and children could not be protected from the early loss of siblings. In Lutterworth, an area well outside the overcrowding and deprivation of growing Victorian cities, more than 12% of infants did not even reach their first birthday; in Manchester in the 1860s, the figure was nearly 21%. The Marriott family of Cotesbach Hall were more affluent than most but were not immune; there was a dead baby in 1866 and the loss of 7-year-old Frederick from diphtheria in 1858.

The most resonant early death of all happened only a few months after our document was written and is doubtless why the little text was kept. Robin Marriott, the oldest son of his generation and therefore the heir to the Cotesbach estate, had just attained his majority and was studying at Oxford when a dreadful accident befell him. During an attempt to climb from his window to that of a friend in a neighbouring second floor room, Robin fell thirty feet to the stone flags of the quadrangle. His parents were informed by telegram and set out with all haste but their quest was hopeless; as their own telegram from Oxford to Cotesbach (preserved in the Archive in draft form) reports, “We are too late. Robin fell while climbing. He never spoke after. Said to have suffered no pain.”

A promising flower had been gathered far too early by ‘the Master’ and the course of Cotesbach history shifted on its axis.

From the Archive: 25th May 2023

The Tichborne Claimant

In a small, leather-bound notebook dating from the early 1870s [doc no .3102] we come across an unusual Archive find – a joke.

Riddle: Why is Kenealy like the Claimant?

Because they are both famous for Wapping relations.

As we all know, a joke that has to be explained is no joke at all; a closer examination of this one, however, reveals an interesting piece of history.

The ‘Claimant’ was the Tichborne Claimant whose story was a sensation in the British press for years, whose court case was one of the longest in the annals of the justice system and whose stage career left its mark on the English language.

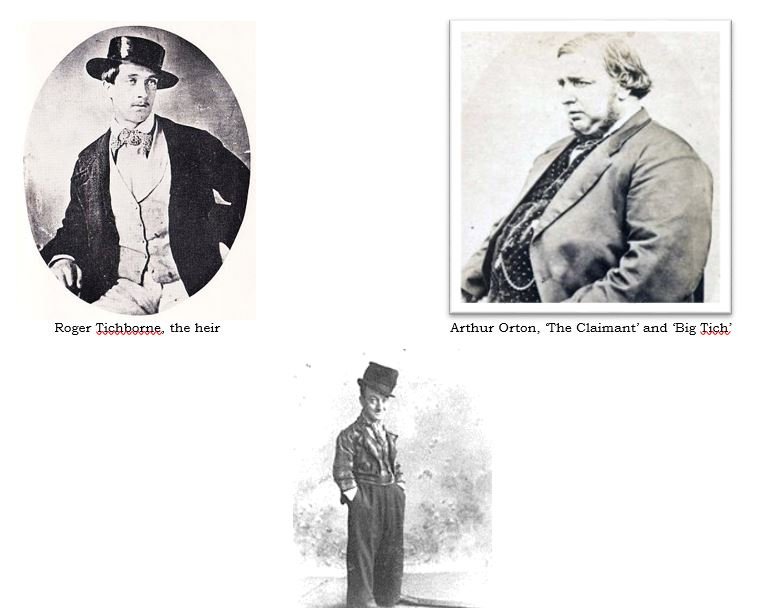

The tale begins in 1854 when Roger Tichborne, the heir to an English baronetcy and a considerable fortune, was lost at sea somewhere between Rio de Janeiro and Jamaica. The wreckage of his ship was found but not a single survivor, although there were rumours that some of the passengers had been rescued by a passing vessel and taken to Australia. Roger’s mother clung to that hope and advertised in Australian newspapers for reports of possible sightings of her tall, willowy and slightly effeminate son. In 1865 (when Lady Tichborne had added to her advertisements the fact that her husband had now died, leaving Roger the extensive family estate in Hampshire), an Australian immigrant living in Wagga Wagga came forward to claim his inheritance.

Members of the Tichborne family and staff were unconvinced by the burly and semi-literate ‘Claimant’ who spoke with a marked Cockney accent but Lady Tichborne was completely taken in. She championed him until her death in 1868 but then he was forced to do battle with the less gullible members of the family through the courts. To cut a very long story short, the Claimant was eventually exposed as one Arthur Orton, a butcher whose family still lived in Wapping, and was sentenced to fourteen years’ imprisonment. His eccentric defending counsel, Edward Kenealy, was reproved for his scurrilous and mendacious conduct during the trial.

Orton continued to maintain his innocence and, for some years after his conviction, enjoyed a degree of support amongst the British populace. This had dwindled to almost nothing, however, by the time he was released from prison in 1884 to a life of destitution and eventual obscurity. For a few years he scraped a living by performing as ‘Big Tich’ in circuses and music halls; in reference, no doubt, to the stark contrasts between the Claimant and the real Roger Tichborne, an existing music-hall artist called Harry Relph (who was just 1.37 metres tall) adopted the stage name ‘Little Tich’, thus giving the English language the expression ‘titchy’.

This is almost the only trace now of a Victorian sensation – a word in the dictionary…and, of course, a joke in an old notebook.

Riddle: Why is Kenealy like the Claimant?

Because they are both famous for Wapping relations.

Orton was exposed as having family roots in Wapping; Kenealy was censured for the ‘whopping’ tall stories he told in Orton’s defence. Get it now? Oh, well ….

From the Archive: a Victorian Obsession

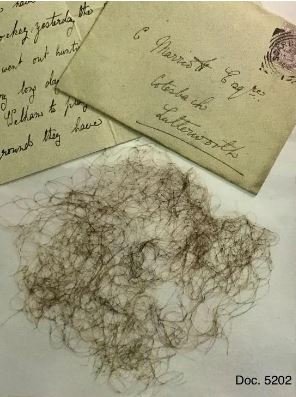

Curiously, several Archive documents contain locks of hair. Here is an example from 1844, sent from Tasmania to Cotesbach with news of a birth; a lock of the baby’s hair is carefully sewn to the page.

Queen Victoria’s mourning brooch

containing a lock of Albert’s hair.

In Victorian times hair was almost an obsession, snipped from both living and dead and kept in lockets, in frames or woven into jewellery. In an era before photographs were easily available, hair became a tangible and intimate connection between people, a treasured keepsake when loved ones were far away or ‘gone before’.

The Victorians were not the first to revere hair in this way, of course. After the execution of Charles the First in 1649, his supporters cherished locks of his hair which were often worn beneath clothing in a closed and secret locket. It was the Victorians, however, who made the cult public; in 1854 Wilkie Collins wrote that hair jewellery was, “in England, one of the commonest ornaments of women’s wear.” When Prince Albert died in 1861, Queen Victoria had eight pieces of mourning jewellery created using locks of his hair and was never without at least one of them for the remaining forty years of her life.

…None of which explains why an archived letter of 1900 contains a hairnet!

Letter of 1900 containing a hairnet.

From the Archive: An “Arctic fairy land”

A letter sent from Cotesbach on the 5th February 1917 contains a magical description of some wintry weather:

“Seven inches of snow fell, and as there was scarcely any wind, there has been a wonderful bit of scenery all today, and now in the bright moonlight. For the shrubs and trees are laden with very thick but very light snow, and it is like a sort of Arctic fairy land. I suppose you have been having skating, and the ice ought to be very strong.”

February 1917 was the coldest month of the winter in the United Kingdom, registering the lowest temperatures for more than twenty years. It ranked as the fifth coldest February of the whole 20th century. The thermometer readings at Cotesbach were by no means exceptional for the Midlands; writer Charles Marriott noted an overnight temperature of 4 degrees Fahrenheit (-15.5 C) on the 5th February and on the same night 2 degrees F (-16.6 C) was recorded in Benson, Oxfordshire. Charles’s son Jem (James Edmund Marriott of the Royal Flying Corps, serving in France) had also reported “28 degrees of frost”, or -15.5 degrees C, and parts of Continental Europe were even colder.*

The effect on soldiers in the trenches of WW1 are beyond imagining. What follows is an account by NCO Clifford Lane, quoted on the website of the Imperial War Museum:

“The coldest winter was 1916-1917. The winter was so cold that I felt like crying.... I’d never felt like it before, not even under shell fire. We were in the Ypres Salient and in the front line, I can remember, we weren’t allowed to have a brazier because it weren’t far away from the enemy and therefore we couldn’t brew up tea. But we used to have tea sent up to us, up the communication trench....It would start off boiling hot; by the time it got to us in the front line, there was ice on the top it was so cold.”

After long weeks of such privations, of exposure and frostbite, a thaw set in – and the notorious, deathly mud returned with a vengeance. It seems a very long way from the “Arctic fairy land”, yet Cotesbach did not remain untouched by the war. The letter is on black-edged paper for two sons already lost.

* The Meteorological Office has an on-line archive with (amongst other fascinating items) historical weather reports, searchable by date:

https://digital.nmla.metoffice.gov.uk/archive